The Japanese Ivy Cult

|

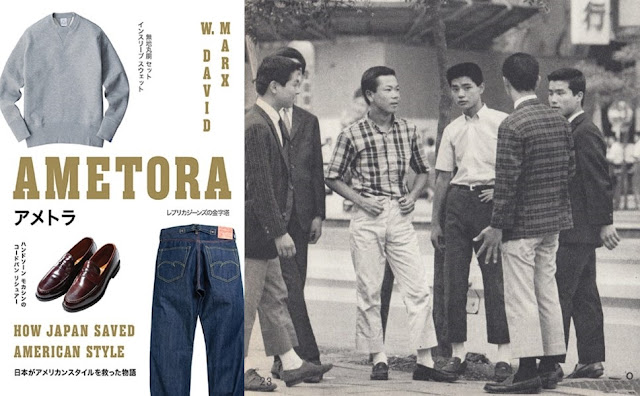

| The Miyuki-zoku, a 1960s Japanese youth movement that revolved around Ivy Style clothes (Source: www.putthison.com) |

In the United States, Ivy League style was steeped in tradition, class privilege, and subtle social distinctions. No one read manuals on the style—they just imitated their fathers, brothers, and classmates. In Japan, VAN [1] needed to break down Ivy into a distinct protocol so that a new convert could take up the style without having ever seen an actual American. The resulting pedantry, however, risked turning Ivy’s youthful energy into sheer tedium. Back in the U.S., the best part of collegiate fashion was its unconscious cool. Men’s Club often gave the same styles the fun of filing taxes.

Yet Men’s Club readers ate it up, and their demand for instruction only resulted in an even greater tyranny of details. A true “Ivy shirt” had a small “locker loop” under the collar and a center box pleat. Ivy men wore a pocket square in the “Ivy fold,” a necktie exactly 7 cm wide, and an “orthodox” pant length. A biblical dogma developed about the Ivy suit jacket’s center hooked vent, even though its presence on the back of the jacket made it mostly invisible. Men’s Club, meanwhile, warned against the danger of slanted jacket pockets—a nefarious “anti-Ivy technique.” Beyond spreading knowledge about Ivy clothing, this homosocial one-upmanship brought fashion—previously belittled as a “feminine” pursuit—closer to technical “masculine” hobbies such as car repair and sports.

In 1963, Kensuke Ishizu [2] laid down the master concept for Western dress in Japanese with just three letters: “TPO,” an acronym for “time, place, occasion.” Ishizu believed that men should choose outfits based on the time of the day and season, their destination, and the nature of the event. Ishizu was certainly not the first to think about fashion in terms of social context, but this simple phrase “TPO” (tī pī ō, in Japanese) set it as the central principle for how the Japanese adopted American style.

TPO made particularly good sense with Ivy, which represented a comprehensive fashion system rather than a single look. One could be Ivy in class, Ivy at church, Ivy playing football, Ivy watching football, Ivy as a wedding guest, and Ivy as the groom. TPO also resembled the rules on wearing kimono and other traditional Japanese garments, making Ivy not sound so alien after all.

Ishizu later formalized the TPO idea with a guidebook called When, Where, What to Wear. The pocket-sized volume offered lists of ideal outfits, coordination styles, and fabric types, as well as diagrams on how to get the perfect suit fit. Ishizu also wrote up short essays on proper looks for all occasions—long trips, short trips, European and Hawaiian vacations, U.S. business trips, PTA meetings, blind dates, ice skating excursions, and bowling nights. The book was an immediate best seller. Electronics maker Sony passed out copies to every male employee.

With these writings, Ishizu hoped to relay his conviction that Ivy fashion was not a fleeting industry trend but the path towards a noble way of life. Seeking to avoid the waxing and waning of so many previous fashion trends, he famously proclaimed, “I don’t make trends—I want to create new customs.”

- VAN or VAN Jacket Inc. was a Japanese clothing brand that started the Ivy trend in the 1960s

- Kensuke Ishizu was the founder of VAN Jacket Inc.

Comments

Post a Comment